Historia

¿Qué sucedió en Arganda en 1613?

El Motín de Arganda es un suceso que tuvo lugar en la villa de Arganda los días 12 y 13 de septiembre de 1613, con un destacado protagonista, el alcalde Felipe Sanz que encabezó la revuelta popular y el personaje más poderoso del momento, el Duque de Lerma.

Todo comenzó en 1583, cuando los vecinos tomaron la decisión de endeudarse con tal de no ser vasallos del Arzobispo de Toledo. Desde entonces, han pasado más de 30 años desde que Arganda consiguió ser Villa del Rey a costa del sacrificio de pagar 10.200 ducados que los vecinos tuvieron que pedir a dos prestamistas de la Corte. En febrero de 1613 el pago de la deuda se hace insoportable y los vecinos deciden en concejo abierto volver a tener un nuevo Señor. No hubo unanimidad en el concejo, el resultado fue 322 votos favorables frente a 28 vosotros en contra de un grupo de valientes vecinos que con sus nombres y apellidos contradicen la venta y defienden la independencia de la villa.

Jueves, 12 de septiembre 1613.

En otras ocasiones, el Duque había tardado más de un año en tomar posesión de sus nuevas villas, pero en el caso de Arganda no llegó a una semana. El 12 de septiembre de 1613, entra en Arganda acompañado por su tío, el Arzobispo de Toledo, y se dirigen hasta su palacio, la Casa del Rey.

El alcalde Felipe Sanz y el pregonero Gabriel Gómez salen desde la Casa del Concejo en dirección a la calle San juan pregonando a los vecinos que enciendan luminarias en puertas y ventanas por la llegada del Duque de Lerma a la villa.

A mitad de la calle un grupo de cocheros y sirvientes del Duque y del Arzobispo, salen de una de las tabernas y comienzan a insultar al alcalde y al pregonero. Uno de ellos, le golpea en la cara con el pomo de su daga y lo derriba al suelo mientras le rompe la vara de justicia. En este momento se arma un gran revuelo, el alcalde ordena que arresten a todos los cocheros y criados y los lleven a la cárcel municipal. El cochero agresor consigue huir y va hasta la Casa del Rey para contarle al Duque de Lerma lo que había sucedido.

Viernes, 13 de septiembre 1613.

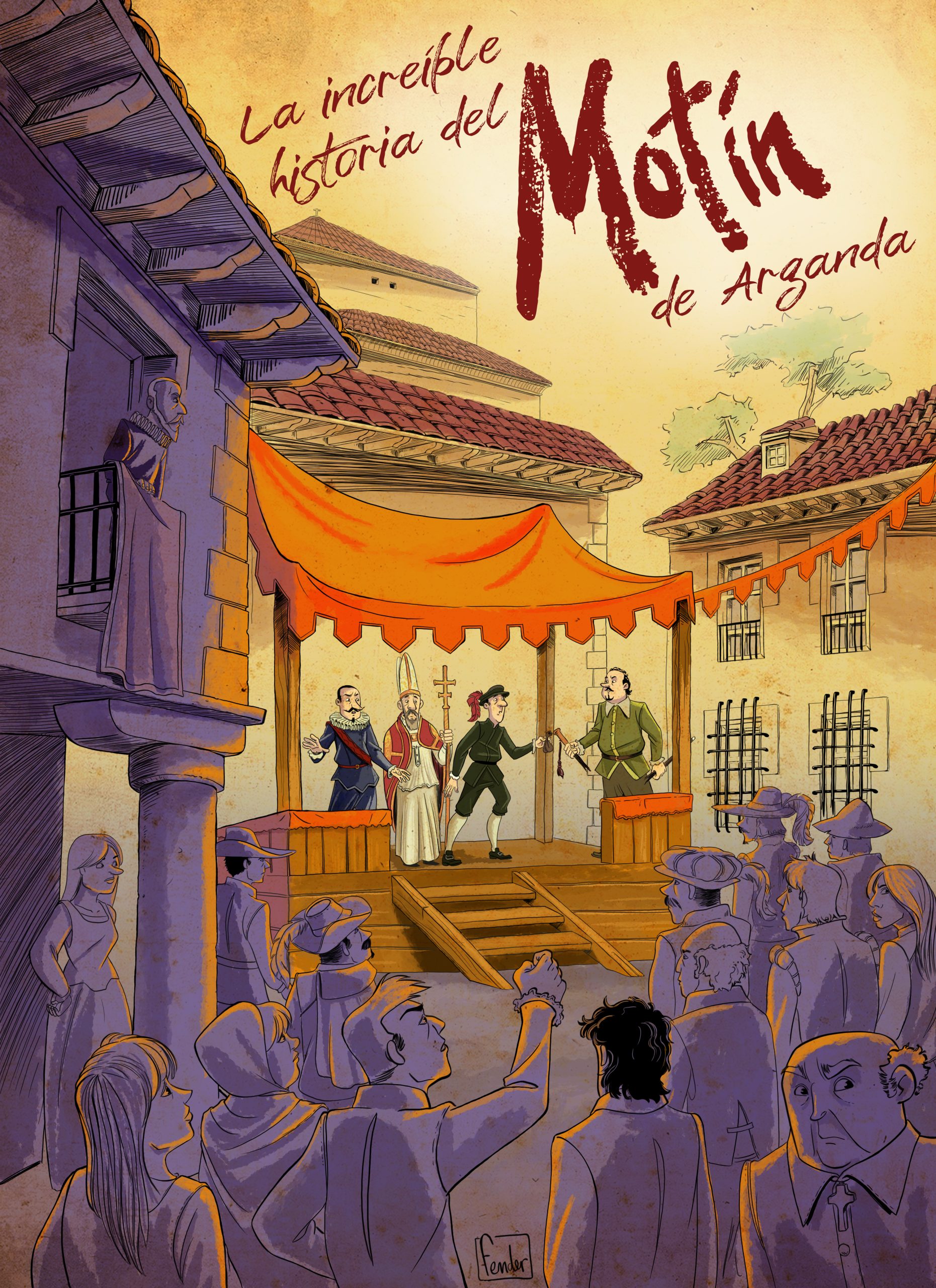

Era un día grande para el Duque de Lerma, por fin podría incorporar Arganda a su señorío y había que celebrarlo. Para ello había mandado organizar unas grandes fiestas sin reparar en gastos y con el punto fuerte de los toros. Arganda esos días era un hervidero de gente venida de todo Madrid, incluyendo a Miguel de Cervantes, al ser protegido del Arzobispo de Toledo su presencia en la toma de posesión era obligada.

A primera hora de la mañana, el Duque y el Arzobispo se dirigen hasta la Casa del Concejo para tomar posesión de la villa. El Duque no las tenía todas consigo, estaba preocupado por la situación de la noche anterior, y decide preparar una bolsa con 200 escudos y cuando llega a la plaza y divisa al Alcalde, era fácil reconocerlo por el labio partido, detiene el carruaje y envía a su cochero para ofrecerle la bolsa de dinero. El Alcalde, sorprendido y agraviado por este gesto de desprecio hacia lo que simboliza su cargo, rechaza la bolsa diciendo a voz en grito que “el agravio se ha hecho a la vara”. En ese momento, los vecinos que han sido testigos de este despectivo gesto del Duque se levantan contra él, se arma un gran revuelo, que acaba con un amotinamiento y levantamiento popular, y la muerte repentina del cochero y el Duque resulta magullado y golpeado.

Esa tarde, mientras que el cochero era enterrado en la Iglesia parroquial, el pueblo disfrutaba de las fiestas. Sin embargo, El Duque y el Arzobispo tenían pocos motivos para celebraciones, estaban abochornados, magullados y con la mayoría de sus criados y sirvientes presos, contaban las horas para volver a Madrid.

What happened in Arganda in 1613?

The Arganda Uprising was an event that took place in the town of Arganda on the 12th and 13th of September, 1613. Its main figure was the mayor, Felipe Sanz, who led the popular revolt, and it involved the most powerful person of the time, the Duke of Lerma.

It all began in 1583 when the townspeople decided to take on debt to avoid becoming vassals of the Archbishop of Toledo. Since then, over 30 years had passed since Arganda had gained the status of a royal town, at the cost of a sacrifice: a payment of 10,200 ducats, which the residents had to borrow from two courtiers. By February of 1613, the debt had become unbearable, and the townspeople, in an open council, decided to once again have a lord. There was no unanimous decision; the vote resulted in 322 in favor against 28 dissenters, a group of brave citizens who, with their full names, opposed the sale and defended the town’s independence.

Thursday, 12th of September 1613

On other occasions, the Duke had taken more than a year to take possession of his new towns, but in Arganda’s case, it was less than a week. On the 12th of September 1613, he entered Arganda, accompanied by his uncle, the Archbishop of Toledo, and they proceeded to his palace, the Casa del Rey.

Mayor Felipe Sanz and the town crier, Gabriel Gómez, left the town hall and made their way to San Juan street, announcing to the residents that they should light torches on their doors and windows in celebration of the Duke of Lerma’s arrival in the town.

Halfway down the street, a group of coachmen and servants of the Duke and the Archbishop emerged from a tavern and began insulting the mayor and the town crier. One of them struck the mayor in the face with the pommel of his dagger, knocking him to the ground and breaking his staff of office. At that moment, a great commotion ensued, and the mayor ordered the arrest of all the coachmen and servants, who were taken to the town jail. The attacking coachman managed to escape and went to the Casa del Rey to tell the Duke of Lerma what had happened.

Friday, 13th of September 1613

It was a grand day for the Duke of Lerma, as he was finally to incorporate Arganda into his lordship, and this called for a celebration. He had ordered great festivities without sparing expense, with the highlight being a bullfight. During those days, Arganda was teeming with people from all over Madrid, including Miguel de Cervantes, whose presence at the ceremony was almost obligatory due to his protection by the Archbishop of Toledo.

Early in the morning, the Duke and the Archbishop headed to the town hall to take possession of the town. The Duke was uneasy, troubled by the previous night’s events, so he decided to prepare a pouch containing 200 escudos. When he arrived at the square and spotted the mayor, easily recognizable by his split lip, he stopped his carriage and sent his coachman to offer the mayor the money. The mayor, surprised and insulted by this gesture of contempt for the symbol of his office, refused the pouch, shouting loudly that “the offense was done to the staff.” At that moment, the townspeople, witnessing the Duke’s disdainful gesture, rose against him, and a great uproar ensued, resulting in a popular uprising, the sudden death of the coachman, and the Duke being bruised and beaten.

That afternoon, while the coachman was being buried in the parish church, the townspeople enjoyed the festivities the Duke had arranged to celebrate becoming the new lord of the town. However, the Duke and the Archbishop had little cause for celebration. They were humiliated, bruised, and most of their servants and attendants were imprisoned. They were counting the hours until they could return to Madrid.